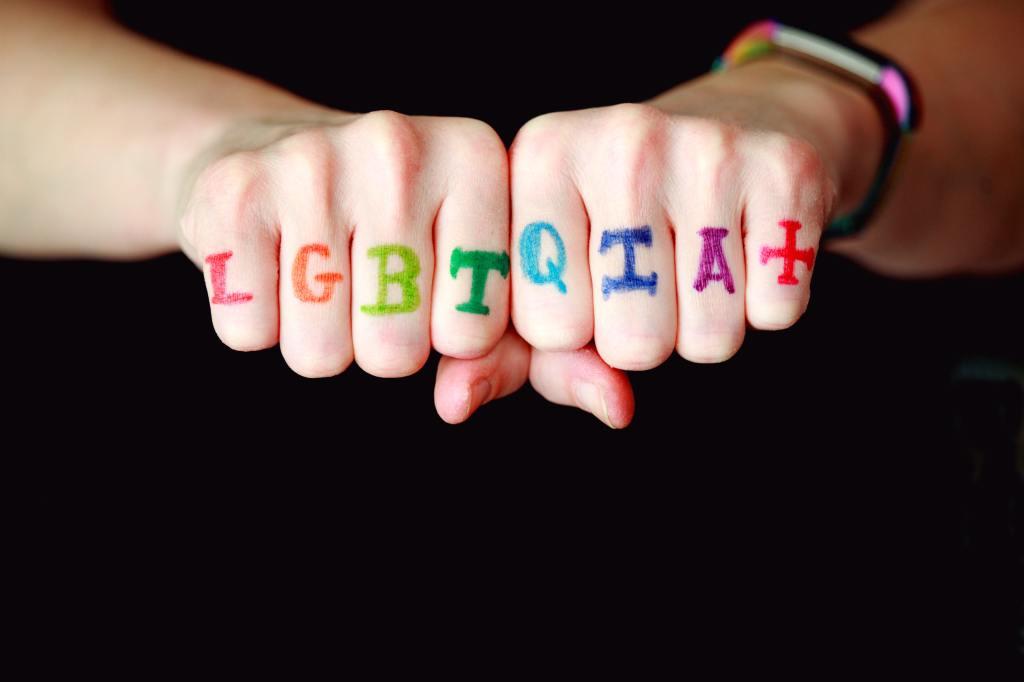

You might have read my earlier blog post about the language I’m using in my research, where I discussed why I’m using the word ‘queer’ in the title of the research, and why I use it to describe myself. (If you haven’t read that – check it out here).

Almost as divisive and controversial is the use of the term ‘family carer’ or similar, used to categorise or define someone who supports and cares for a person in their own home. In an Irish context, the term ‘family carer’ seems to be the consensus over and above other terms used elsewhere such as ‘informal carer’ or even the arguably simpler ‘carer’ or ‘caregiver’. This is because here, often, people see the word ‘carer’ and assume someone who is paid a wage to provide care, perhaps via the Home Support Scheme or similar. By using the term ‘family’ alongside ‘carer’, the hope is that enough of a delineation is made – but of course that also means that if you’re caring for a friend or neighbour, you might not see yourself in that language.

Embracing the identity of family carer is often what enables someone to start to access supports for their caring journey – without fully understanding that you are a carer, and that you have your own needs, it’s easy to become overwhelmed, burnt out, frustrated and angry. These are totally natural emotional responses, but tapping in to the supports available – scant though they might be – can help alleviate some of these negative emotions and experienced.

In 2017, I published a paper in the International Journal of Care and Caring; Defining and profiling family carers: reflections from Ireland. That paper, although a few years old at this stage, discusses some of the points that must be taken into account when discussing the idea of language use and it’s relation to caring supports and services.

In this Doctoral study, as I am looking at the experience of queer carers, the use of the term ‘family’, can, in some cases, cause confusion. Do I mean only those who are caring for a parent, grandparent, child or other blood relative? Of course not. The idea of family of choice is paramount in the research, in particular when we look back to the AIDS epidemic in the 1980’s and 90’s, where gay men were often cared for and nursed not by medical professionals, but by members of our own community, by lesbians, bisexuals, trans men and women, and other gay men. Past lovers, friends, community elders, all came together to provide the care that was needed. To erase that from the concept of care within the queer community would be a terrible mistake.

So, when I use the term ‘family carer’, I am referring to anyone providing care or support for a disabled person, a person with a chronic illness, long term condition, addiction, or dementia. The care provided does not have to be ‘medical’ in nature, it does not mean you have to be washing and bathing and changing dressings or administering medication. It simply means that you provide a level of support in tasks and at a personal level above and beyond what could be expected of a similar relationship.

If you have any thoughts on this, I’d love to hear from you. And don’t forget, my survey is STILL open for responses – you can click here to get more information.